Turn Your Idea Into A Market-Ready Product.

From patent protection to licensing, we help bring your invention to life with expert guidance.

Inspire, Empower, Succeed.

Unleash Your Business Brilliance.

Since our founding, we've dedicated ourselves to helping independent inventors navigate the challenging path from initial concept to market success.

Our approach combines rigorous intellectual property protection with strategic licensing opportunities, creating a pathway for inventors to see their ideas reach consumers while maintaining their rights and maximizing their earning potential.

Watch Our Inventions in Action

Our Core Services

Real Inventors. Real Success Stories.

High Tide Home

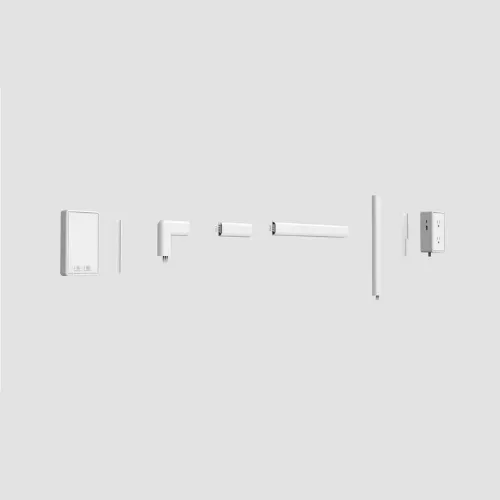

Extension Outlet

Engineered Floors

Get In Touch.

7950 NW 53rd St #337, Miami, FL 33166

Mon – Fri 9:00am – 7:00pm

Sat - Sun CLOSED.

+1 786-550-5298

Ready to Make Your Idea a Reality?

Take the first step toward bringing your invention to market. See if your idea qualifies for our licensing program by scheduling a confidential consultation with our invention specialists.

© 2025 Own My Ideas, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Own My Ideas is committed to ethical inventor services and adheres to the guidelines established by the United Inventors Association.

QUICK LINKS

CUSTOMER CARE

CUSTOMER CARE

LEGAL

© Copyright 2025. Own My Ideas. All Rights Reserved.

Facebook

LinkedIn

Youtube